For Space

What is space exactly? Something we simply move through and exist within? That houses and contains us? Space is often quiet, unobserved; the unmarked backdrop against which we live out our lives. It surrounds us, yet we miss so much. Allow your eyes and mind to adjust, however, and even the most seemingly unremarkable of spaces will reveal a deep richness. A complex tapestry of layered nuances waiting to be discovered. It’s this closer, more attentive kind of looking and perception demanded by the meditative act of drawing that unites each of the nine artists’ work in For Space, along with a shared emphasis upon research, encounter and engagement. Overall, the show seeks to bring about a deeper understanding of the phenomenon, capturing it in its truest form – described by the curator, Simon Woolham, as “shards of lived experience.”

This experiential quality is found in Gerry Davies’ depictions of the caves and passages of North Yorkshire, for example. Made through a series of site visits and sketches, each pieces is more a portrait of the psychological and sensory conditions of that environment, captured through various shifting angles, rather than a strictly accurate geographic or visual representation. The same foregrounding of experience resurfaces differently in the work of Jack Brown, by contrast. Of his two pieces in the exhibition, one shows the artist’s hand drawing a house in his hometown (Stockport), while the other shows his whole person engaged in the act of posting the image through the house letterbox. As such, we encounter Brown’s existence within the space and moment of each picture from two perspectives: his own in the first, and that of an onlooker (or his own imagined view of himself) in the second. Together they add up to the deceptively simple claim: “I was here, engaged in this act;” whilst simultaneously conflating time, space and experience.

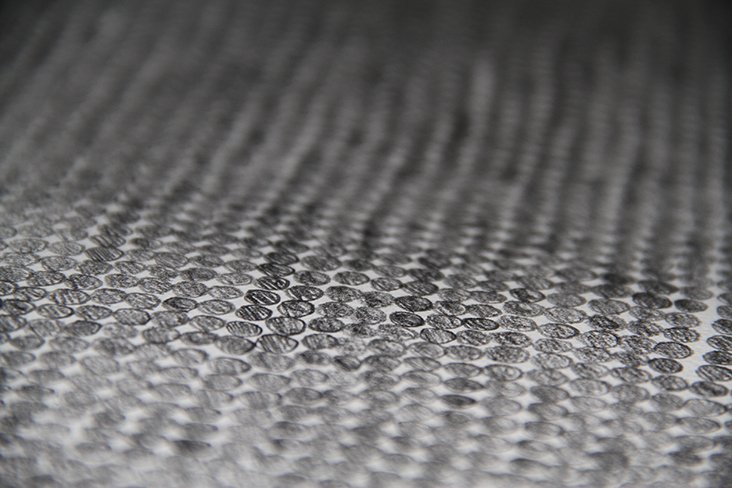

This performative aspect of Brown’s work features in many other pieces in the show, though perhaps most clearly in Tom Baskeyfield’s stone rubbings and Anna Barriball’s Night Window (2013) (created by placing paper on textured glass covered in black ink, then ‘developing’ the image by bathing the paper in an ink-water solution). Both pieces are at once records of surface and action combined. Through the two artists’ different techniques, each attempts to bring us into as direct contact with the original object as possible, in Woolham’s words: highlighting “the liveness of the event by engaging with space.”

A similar interest in exploring different methods of drawing as a tool for representing the exhibition’s theme echoes throughout. Some of the works fall into the three-dimensional realm of sculpture, such as Woolham’s Up Against the Rule (2017) – made of both a tree stump, ruler and rock, and the artist’s biro drawings of these objects. Others tap into drawing’s ability to offer a more immediate, less filtered connection between mind and action, allowing for something akin to a stream of consciousness to spread across the page. James Steventon’s 13 Hours with Weighted Vest (BST) (2017) takes this concept a stage further; the piece being the end result of a private endurance-based performance in which the artist ‘drew’ the patterns of his breathing whilst wearing a weighted vest (mixing drawing as action and noun).

Part of her ongoing Index Drawings series, Layla Curtis’s two hand-drawn maps explore this idea of translating inner, mental experience in a slightly different way. Both pieces show areas of Paris stripped of all graphic information except street names, raising questions around how we have come to engage with, navigate and conceptualise space through plotting and semantics. By comparison, Hondartza Fraga’s life-size drawing of a section of Mars confounds any internalised images we might have of this alien environment by confronting us with its physical reality. It also draws attention to the degree to which our human understanding of space has shifted overtime in line with advancements in technology. We can now accurately capture the landscape of other planets, or interact with people on the other side of the world via the internet. Human scale and global scale have collapsed in one each other.

This interest in our changing relationship to our surroundings lies at the heart of ‘For Space’ (2005), the last collection of essays by the Wythenshawe-born radical geographer and social scientist, Doreen Massey, to whom the exhibition is dedicated and whose ideas thread throughout. Woolham (who, by chance, discovered he was born and grew up on the same street as Massey, and was later remembered by her) has been heavily influenced by the academic, both in terms of his own writing on the subject and artistic/curatorial practice. His interactive, downloadable hand-drawn App artwork, School (2004), for example, taps into the way that the virtual world now mirrors or (in this case) ‘ghosts’ the physical. The piece allows users to wander around and get lost in the artist’s old secondary school (which was demolished in 2011), re-living or experiencing memories of some of the incidents and events that went on during break-time, as well as uploading and mapping their own. Described by Woolham as a sort of ‘friends reunited’, the concept draws attention to how the internet has in some sense allowed humans to transcend the time-space dimension.

In a similar (analogue) vein, Jenny Steele’s screen-print, A Sea Outlook (2017), is part of a wider body of works that revive and restore certain original features from Morecambe’s iconic, 1930s Midland Hotel that were destroyed during the building’s life. Her process is based upon detailed architectural research which, as Woolham describes, “makes associations and links between lineages of cultural representation, resulting in new works that embody and interpret timescales.” Like School, the work offers a window into a space no longer physically present or accessible to us. Baskeyfield equally reanimates the past – thus relocating it in the present – in his two pieces Ifan and Owen (2016/7), as the detailed textural quality of each stone’s surface, illuminated by the rubbing process, tells the story of thousands of years of rock formation and geographic shifts.

To draw awareness to the nuances, complexities, and presence of space seems particularly valuable in an age of aggressive land privatisation, digitisation, overcrowding, anonymous globalisation, and cultural and ecological destruction. Though these themes may not all be explicit in For Space, the lessons the exhibition provides (through the deceptively simple art of drawing) help to equip us in a more perceptive, attentive kind of engagement with the evolving physical and psychological conditions of the present. To become active citizens of space.